Understand the Linux Kernel Image formats

Understand the executable file and Linux Kernel Image formats in various platforms.

Targets:

- Understand executable file formats like binary, ELF, and PE.

- How bare metal images are loaded in embedded system.

- Understand Linux kernel image formats and how they are loaded.

1. Executable file formats

1.1. Binary

Executable binary files is nothing but a sequence of bytes. These files contain no additional information to execute. To execute them, the executable file loader MUST know where to locate the binary and where to start executing. That means the loader and the compiler have to deal with each other to exchange these information in some way.

The embedded systems are mostly using this way, for example, we flash the binary file onto well-known address, let’s say, FLASH memory starting point 0x0800 0000, where the CPU will automatically start executing after a reset. In that case, the execution entry point will be at the same address. The flasher have no idea about these addresses, we must to specific them ourselves.

1.2. ELF

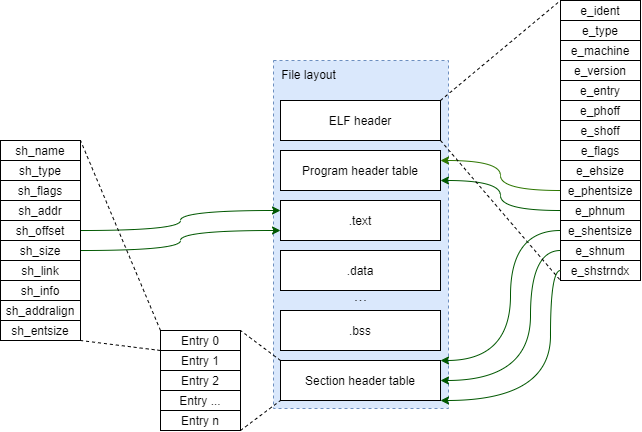

Executable & Linkable format (aka. ELF) is a standard file format for executable files. Unlike raw binary files, The ELF image contains metadata that describes itself. Each ELF file includes four parts:

- ELF header, basic executable file information, entry point, and info to get program header table and section header table.

- Program header table, describe memory segments.

- Section header table, describe sections.

- Program Sections.

First thing first, the ELF header is located at the beginning of the ELF file. Start with magic numbers and followed by basic information like type, machine, version, etc. The ELF header also contains e_entry this is the memory address of the entry point from where the process starts executing. Other important fields are, the e_phoff that points to the program header table and the e_shoff that points to the section header table. By using them, the loader can locate these tables location in the ELF file.

Program header table contains memory segments that are used for runtime execution of the file, it tells the loader how to create a process image. Whereas, the section header table is used for locating sections on the file image and explaining them.

There are some special sections do special jobs. For example, SHT_DYNAMIC section holds the information for dynamic linking, for example, shared libraries. SHT_SYMTAB holds a symbol table, that might be useful for debugging.

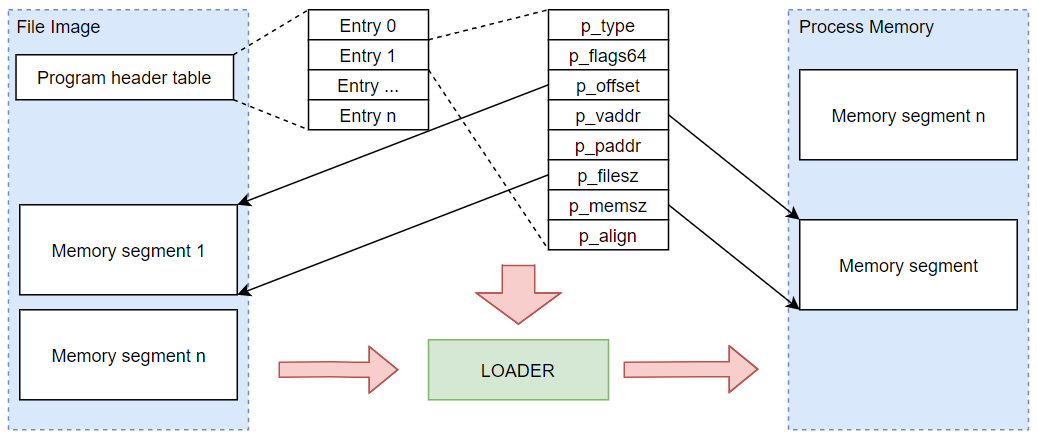

1.2.2. Loading an ELF

- The loader reads the ELF header, validates, and locates the program header table.

- Creates a process memory, loads loadable segments (

p_typeequalPT_LOAD) into memory based on the entry on the program table. The entry contains all the information to load the segment into memory, for example, the memory permission (read/write/executable) and the virtual memory address. - Load dynamic linking programs, shared libraries if required (in

SHT_DYNAMICsection). - Pass the CPU control at the entry point

e_entryto start the program.

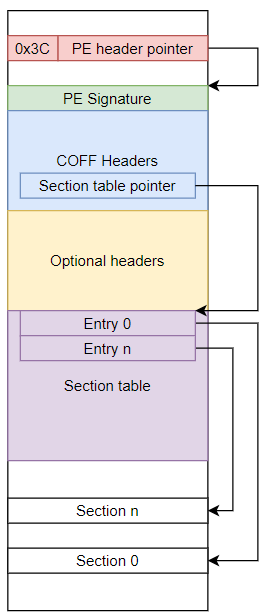

1.3. PE

Similar with ELF, Portable Executable (PE) is an executable file format. But instead of using on Unix-like OS, PE is used mostly on Windows. The PE don’t have the program header table, instead, all the information is described in section header table. The loader based on that to bring sections onto memory.

Unlike the ELF format that puts ELF header at the beginning, the PE format put the PE header address at the offset 0x3C.

The PE format is also the accepted standard for executables in EFI environment according to the EFI specification.

1.3.1. Microsoft PE/COFF

Common Object File Format (COFF), is used for storing compiled code, such as outputted by a compiler or a linker. It is not necessary to be an executable, the COFF file can be used to store individual functions or symbols, fragments of programs, libraries or entire executables.

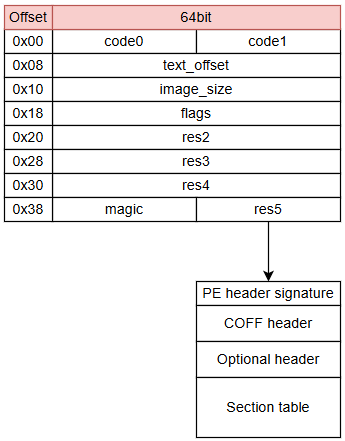

The Microsoft PE Executable format (PE/COFF) contains a version of COFF. Normally, the COFF file puts the COFF header at the beginning. But in case of PE/COFF, if the file is an executable, COFF header is not placed at the beginning. PE/COFF image contains a pointer at offset 0x3C which points to the PE header, and the COFF header immediately follows this PE signature.

The PE/COFF image might look like this:

2. Linux kernel image formats

Linux kernel image might have different format for each architecture. The format, normally, is just a binary image containing machine code for the target architecture. It’s kind of statically linked executable, once loaded onto the memory, it should be able to execute without any helper. This is because there is no OS running before the kernel to check and link dependencies. Once the kernel running, it can load other modules itself.

The bootloader (any software that runs before kernel) is not supposed to do complex tasks. Depending on the architecture, they can do more specific tasks, but the main tasks should be:

- Setup and initialize memory.

- Load the kernel image into memory.

- Call the kernel image.

Other steps like setup device tree, load initrd, decompress a compressed kernel image, etc. might be optional and not mandatory for all bootloader implementation.

Once the kernel running, it can load whatever needed by itself.

Even in binary format, the image still need to provide some basic information so that the bootloader can do its job. The information at least include:

- Kernel entry point.

- Image load offset.

- Magic number to determine.

Now let’s go through popular architectures to see how they implement their image format.

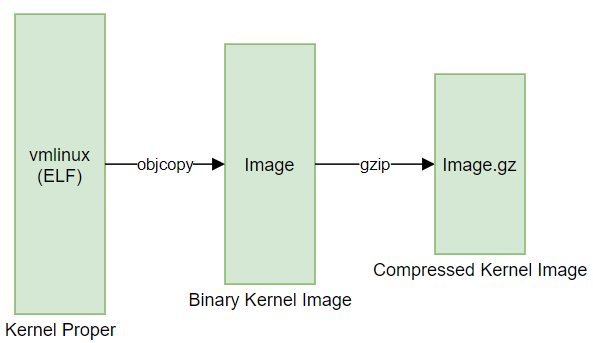

For most architecture, the Kernel build system output an ELF file

vmlinux, that is not able to boot, but contains all information (binary, debugging, symbol table, etc.). By using this kernel proper file, each architecture can produce various kind of kernel images.

2.1. AArch64

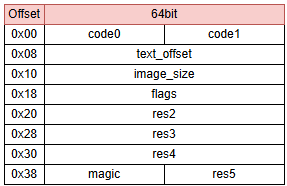

The decompressed kernel image contains a 64-byte header as follows:

The bootloader, for instance, UBoot parses these header to load the kernel into memory, and jump to kernel entry point. UBoot only checks for magic and uses text_offset, image_size, flags to load the image and jump to kernel. Other fields might be ignored.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

#define LINUX_ARM64_IMAGE_MAGIC 0x644d5241

struct Image_header {

uint32_t code0; /* Executable code */

uint32_t code1; /* Executable code */

uint64_t text_offset; /* Image load offset, LE */

uint64_t image_size; /* Effective Image size, LE */

uint64_t flags; /* Kernel flags, LE */

uint64_t res2; /* reserved */

uint64_t res3; /* reserved */

uint64_t res4; /* reserved */

uint32_t magic; /* Magic number */

uint32_t res5;

};

int booti_setup(ulong image, ulong *relocated_addr, ulong *size,

bool force_reloc)

{

struct Image_header *ih;

uint64_t dst;

uint64_t image_size, text_offset;

*relocated_addr = image;

ih = (struct Image_header *)map_sysmem(image, 0);

if (ih->magic != le32_to_cpu(LINUX_ARM64_IMAGE_MAGIC)) {

puts("Bad Linux ARM64 Image magic!\n");

return 1;

}

/*

* Prior to Linux commit a2c1d73b94ed, the text_offset field

* is of unknown endianness. In these cases, the image_size

* field is zero, and we can assume a fixed value of 0x80000.

*/

if (ih->image_size == 0) {

puts("Image lacks image_size field, assuming 16MiB\n");

image_size = 16 << 20;

text_offset = 0x80000;

} else {

image_size = le64_to_cpu(ih->image_size);

text_offset = le64_to_cpu(ih->text_offset);

}

*size = image_size;

/*

* If bit 3 of the flags field is set, the 2MB aligned base of the

* kernel image can be anywhere in physical memory, so respect

* images->ep. Otherwise, relocate the image to the base of RAM

* since memory below it is not accessible via the linear mapping.

*/

if (!force_reloc && (le64_to_cpu(ih->flags) & BIT(3)))

dst = image - text_offset;

else

dst = gd->bd->bi_dram[0].start;

*relocated_addr = ALIGN(dst, SZ_2M) + text_offset;

unmap_sysmem(ih);

return 0;

}

In case of booting though EFI, for compatibility, the res5 (at offset 0x3C) contains the pointer to PE header table, as we discussed before. So this kernel image is a PE/COFF image and bootable in a EFI environment. The full header now might look like that:

EFI firmware, instead of using fields in 64-byte header, it can only need the res5 to jump to PE header start point, using these information to load the kernel, it’s the way kernel make the Image more generic.

To support EFI and PE table, the kernel config

CONFIG_EFIshould be enabled, otherwise kernel will not generate code for the PE header__EFI_PE_HEADER.

After building, the AArch64 Kernel image is placed at

arch/arm64/boot/Image.

2.1.1. Bootable image formats

Image- Uncompressed kernel image that is taken fromvmlinuxwithobjcopy.Image.gz-Imagewith gzip. The bootloader might have to include a decompressor to extract this image. If the decompressor is not available,Imagemight be better choice.image.fit- The Flat Image Tree, that is used mostly by UBoot, is where all binaries (Device Tree, kernel image, initrd) are combined into one.

To check all output formats supported by the Linux kernel for your architecture, run:

make ARCH=<your_arch> helpAnd take a look to theArchitecture-specific targets (<your_arch>)section.

2.2. AArch32

AArch32 bootable image formats:

Image- Uncompressed kernel image that is taken fromvmlinuxwithobjcopy.zImage- Compressed kernel image. Despite this image is compressed, but it’s a self-extracting image. That means, the bootloader don’t have to decompress itself. The kernel, after take control, will decompress automatically.uImage- UBoot wrappedzImage. This image is made from an UBoot utilities also known asmkimage.xipImage- XIP Kernel image.bootpImage- Combined zImage and initial RAM disk.

The self-extracting image is an image that has special headers that contain decompression code. The bootloader read the image header to understand the compression method and decompression instructions. The bootloader then executes the decompression code which will decompress kernel directly into memory.

2.3. x86

bzImage- Compressed kernel image, sometimes it is renamed as avmlinuz. This image is also a self-extracting image.fdimage- 1.4MB boot floppy image.fdimage144- 1.4MB boot floppy image.fdimage288- 2.8MB boot floppy image.hdimage- Create a BIOS/EFI hard disk image.isoimage- Create a boot CD-ROM image.